“Design can change the world.”

When I was in design school, this statement filled me with incredible energy and pride. I felt it in my core. How could I not? Over the last few decades, design — and design thinking — has ascended to the point of being routinely viewed as one of the differentiators for companies and products.

Behind this ascension lies design’s anointed operating system: human-centered design.

The fundamental idea behind human-centered design is that, to find the best solution, designers need to develop an empathetic understanding of the people they are designing for.

Designers do this through user interviews, contextual observations (watching users go about their business in their “normal” life), and a number of other tools that help designers put themselves in users’ shoes. Once you can paint an empathetic picture of a user’s needs, the next step in the process is to identify a few key insights and use those to create a solution.

One famous example is the development of the Swiffer mop. Designers, tasked with improving the process of housecleaning, observed customers cleaning their homes. A key insight was that time was critical. Cleaning often cut into time for other activities, and any time savings would be a boon. Mopping was identified as an especially time-consuming part of cleaning, with multiple steps and multiple pieces of equipment, not to mention waiting for the floor to dry. So designers created a “dry mop” (the Swiffer) that simplified the process and saved time. It was a huge commercial success.

Straightforward enough.

And the process works. Countless products and services that drive our daily lives were either born from this process or dramatically improved by it. Smartphones and many of their apps, social media services like Instagram and Twitter. The darlings of the sharing economy — Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb. Not to mention a litany of physical products.

The way the world works and the way we work in it are fundamentally different today than they were even a decade ago. In large part, this is due to the process of human-centered design.

So, we as designers puff out our chests and carry our heads high knowing that we have the power to change the world.

But, if you step back for a moment, you start to see a problem: We’ve been designing the world, real hard, for decades now and we haven’t made a dent in a single real problem.

What do I mean by “real problem”?

I mean real problems. The big ones. The kind that shake us to the core of our humanity and threaten our long-term viability.

Hunger. Climate change. Poverty. Income inequality. Illiteracy. Bigotry. Discrimination. Environmental degradation. The list goes on.

Right now, there are people in the richest country on Earth who are starving. People who can’t access or afford health care. People who are homeless. That’s the richest country.

Right now, our oceans are choking to death from plastics. Our atmosphere is choking to death from CO2, and we have effectively lost 50 percent of the Earth’s biodiversity.

Guess what: Design hasn’t fixed any of it.

Not even the slightest bit.

And, unfortunately, design won’t fix any of it, because our operating system won’t allow it.

The Problem with Human-Centered Design

Big problems, those that threaten our existence or the stability of our society, are systemic. They coarse through the veins of the entire system. Their causes are widespread and varied, and the people involved represent almost every segment of society.

These kinds of problems are multifaceted. They do not have a silver bullet. There is no “ah-ha” insight hiding out there that will suddenly help us solve the problem and see the light.

Instead, solving these kinds of systemic problems is like trying to contain a wildfire. While you’re working to fight one side of it, the other side has just burned another 50 square miles. You can’t hope to make progress by chipping away at one piece of the problem while ignoring the others.

Eventually, like a wildfire, you try to mitigate as much damage as possible until the weather shifts and a rainstorm comes along, providing a truly systemic solution. A solution that addresses the problem from all sides.

Human-centered design is not architected to solve systemic problems. In fact, human-centered design is architected to solve the exact opposite type of problem.

Human-centered design is all about focus. It’s about observing the big picture and then zeroing in on a manageable set of insights and variables, and solving for those. By definition, this means the process pushes the designer to actively ignore many of a problem’s facets. And this kind of myopic focus doesn’t work when you’re trying to solve something systemic.

A recent study on ride-sharing apps, a category of companies heavy on user-centered design, found that ride sharing adds 2.6 vehicle miles to city traffic for every one mile of personal driving removed. Ride-sharing apps actually make traffic in cities worse.

Ride-sharing companies, like Lyft, were predicated on the idea that they could put a dent in the problem of human transportation by solving for traffic congestion, and they used human-centered design approaches to do it. How could they have gone wrong?

It’s obvious. Human transportation is not a focused problem, it is a significant systemic issue. Through a human-centered design process, ride-sharing apps landed on the insight that getting a cab, or finding a ride, was inefficient in many cities. They focused on this insight and then, as their process is designed to do, shut out the other facets of the problem.

They concluded: “If we can make getting a ride more efficient, less people will drive their own cars, reducing traffic.”

This is the kind of simplified, guiding statement human-centered design produces.

And guess what? Uber and Lyft succeeded in making it easier to get a ride. Human-centered design works for a consumer-facing problem like that. In the process, however, they overlooked other aspects of the transportation ecosystem.

For example, as the study found, many people use non-automobile transportation, like bikes, buses, and trains, specifically because they don’t have a car (and getting a ride is a pain). Once ride-sharing apps made it easier to get a car, people who’d previously used public transportation began to opt for car-based travel. Human-centered design’s myopic focus kept this non-auto population obscured from view during the design process. This is an example of just one of the problem facets left out of the solution.

A user-centered approach is great for figuring out how to make the experience better for Airbnb customers, or how to change the way people mop. But it cannot contain a systemic problem like human transportation. When faced with a big, hairy, multifaceted problem, our focused, iterative operating system is abysmally inadequate. Human-centered design can barely handle damage control.

And so we inch our way forward. Chipping away at one side while the other burns out of control.

What Do We Need Instead?

I’m not saying we need to abolish human-centered design. It works for what it’s designed for. We have way better mops now (among many other things), and that’s wonderful. But, we need to understand the limits of our tools and begin to think about new ones. Tools that can help us grok the breadth and complexity of really big problems — and start to solve for them systemically.

Some in the design field are working on moving human-centered design forward. IDEO, one of the progenitors of human-centered design, is pushing a new concept: Circular Design. The idea behind Circular Design is to start thinking about designed objects through the lens of a “circular economy.” No longer driven by a create and dispose mentality, but a create and reuse mentality. It’s a rebrand of the cradle to cradle concept, focused on sustainability.

While this is an important step forward, it falls short of the systemic design thinking we need. Like the myopic aspect of human-centered design, Circular Design still drives toward focused design insights from which to create solutions. The difference? It asks the designer to consider the full life cycle of a solution and its long-term impact. Again, this is an indisputably important shift in the culture of design, but will it truly solve big problems?

If I design for the full life cycle of my reusable water bottle, I may have a more sustainable water bottle, but I have not created a systemic solution for our plastics problem. I have not changed the economic incentives driving plastic culture. I have not solved for the distribution and financial issues that make single-use bottled water more accessible. I have not solved for the public health issues that make single-use bottled water significantly safer in many areas. And I have not solved for all the other applications of single-use plastics.

I’m back to damage control. And the fire keeps getting bigger.

How Can We Break the Mold?

If we extend the wildfire analogy, perhaps we can create a design framework that allows us to more rapidly innovate in small ways across all facets of a problem, instead of trying to focus on a select few. Like a rainstorm, lots of tiny drops — delivered in a coordinated fashion — can extinguish a very large fire.

Or maybe it’s about getting rid of our culture of competition and creating a new culture of collaboration. If we start ignoring the corporate and political silos separating us, we can collaboratively combine lots of focused solutions, allowing us to knit them together into a single tapestry that truly covers an entire problem. There are lots of solutions out there. We just don’t have a thread pulling them together.

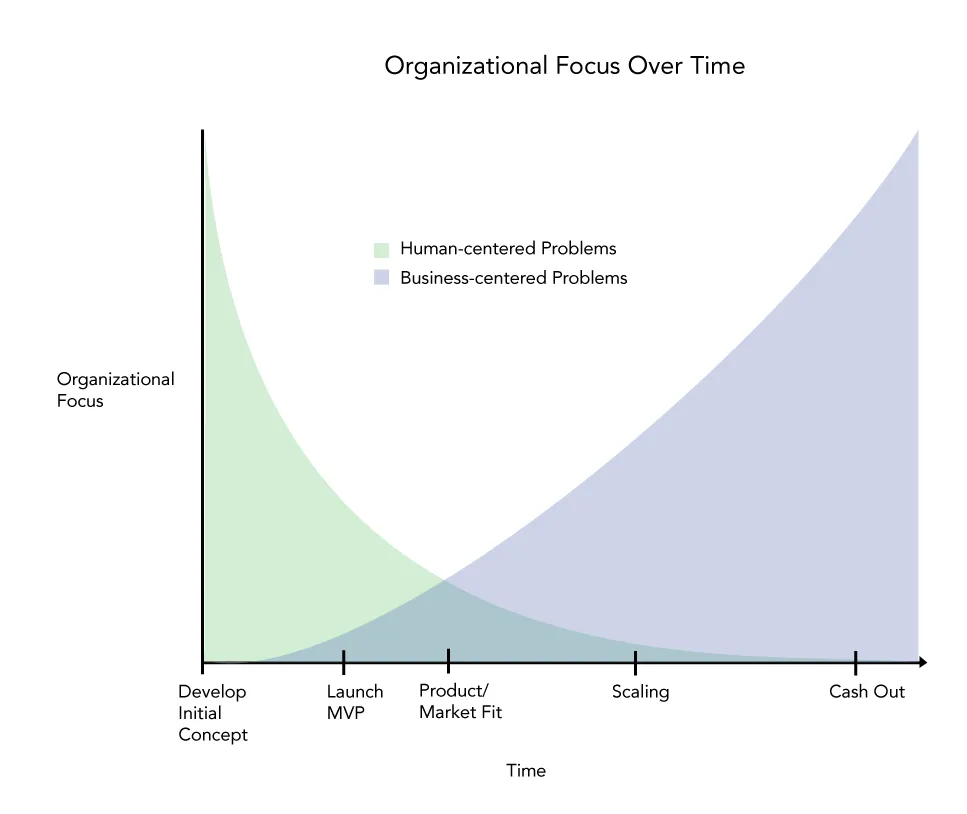

Or maybe it’s about upending the economic incentives that drive design. Human-centered design was created to serve our current economic system. There’s money in creating a better mop. There isn’t money in solving homelessness. In order to thrive economically we needed to consistently design better mops, so we built a framework to do it.

If we had the right incentives, how quickly could we develop a framework for systemic design thinking?

Design can change the world. But the way we’re going about it right now isn’t cutting it. If we want to design our way out of the big issues, we need to take a critical look at our approach. We need to upgrade our innovation operating system.

—

“Design Won’t Save the World” was originally published in Medium on August 1, 2018.