Software is usually designed as a choose-your-own-adventure affair. To complete tasks, users move through an application by making a series of choices based on available options. This can include choosing an item from a menu, choosing the appropriate tool from a toolbar, or selecting a piece of content from a list. The user is always free to decide for themselves, but the design and presentation of these options has the power to greatly influence the choices they make.

In their book, Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein make an argument for what they call “libertarian paternalism” in the design and architecture of choices. The idea is that we can design software that allows a person to make his or her own choices (libertarianism), but that we also have the power to “nudge” that person in the direction of his or her best interest (paternalism). Of course, this means we can also nudge people in a direction that is in our best interest. As Thaler and Sunstein write, “There is no such thing as neutral design.”

As designers, every decision we make has the potential to nudge a user down a specific path. Sometimes, the consequences of these nudges are beneficial. Sometimes they’re not. To create a stellar user experience, we must explicitly define when and how we nudge.

Here’s a simple, two-step framework for deciding when to nudge, how to nudge, and what outcome is “best” in a given choice architecture.

Step 1: Defining the Best Outcomes

Whenever you’re presenting a user with a choice, ask yourself: What are the user’s goals at this point? Which options will best help them achieve those goals? What are the business goals in this situation? Which options best deliver on those goals? Do the user’s best options match those of the business?

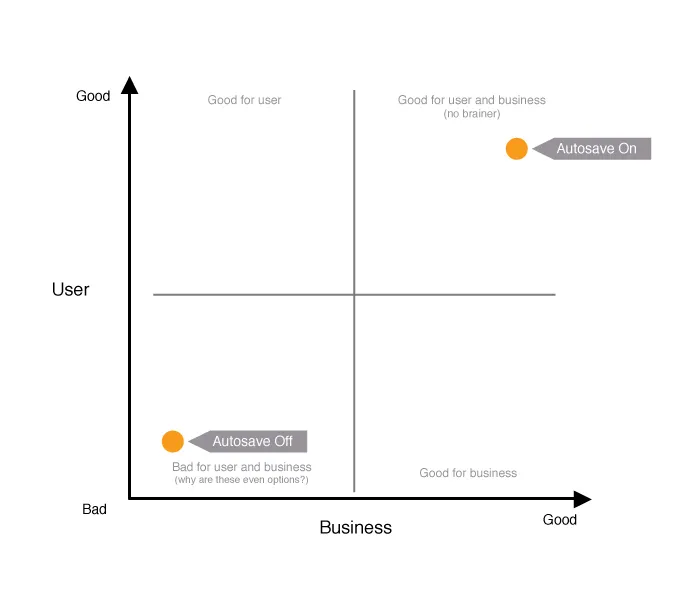

I recommend setting up a two-by-two grid to answer these questions. I call it a choice outcome matrix:

The choice outcome matrix plots possible choices based on their benefit to the user vs. their benefit to the business. Choices that are good for the business and good for the user are no-brainers; your designs should nudge toward these. Choices that are bad for the business and bad for the user should probably be eliminated from the set of options all together. Choices that are good for one but not the other aren’t as simple. Determining the best outcome here is a case-by-case decision. Ask yourself: Do we value the business outcome over the user experience in this case, or vice versa? In these cases, you can also consider what would need to change to better align the two.

Take, for example, a user signing up for a subscription service in which they’re presented with two plan options: a free, ad-supported plan or a premium, ad-free plan at $9.99 per month.

These choices are plotted on the matrix below:

In this basic example, the free plan is better for the user because it’s free. The pay plan is better for the business from a revenue standpoint, but worse for the user because of the cost. (Note: This assumes a pretty benign ad experience. If ads are intrusive, the plot might look different — meaning, it might be worth it for a user to pay to avoid ads.)

How might this matrix influence a final design? Here’s how Spotify handled a similar scenario:

Behold: Nudging by design. In the green button and banner, Spotify is nudging users toward its premium plan, which is best for the business. In this specific scenario, they also added a 30-day free trial and some extra features (offline listening, additional devices) to the premium plan. These extra features help to better align the best choice for the business with the best choice for the user.

Step 2: Choosing How to Nudge

Once you’ve identified which choice represents the best outcome, you then must choose the best approach to encourage that choice. Here are three basic approaches to consider:

- Visual: Spotify is a prime example of a visual nudge. Its designers use color, size, and placement on the page to drive users toward a specific choice.

- Social: Humans have a strong desire to conform. We’re often guided by the actions of others, even if we don’t realize it. Presenting social “proof” of the value of a specific choice can be a strong nudge. Amazon, for example, uses social nudges like customer reviews and ratings to guide users toward purchasing the best available products. Similarly, YouTube displays the number of views a video has received as a subtle social nudge to help you choose videos you’re most likely to enjoy (and engage with).

- Default: Setting something as a default in an application is one of the most powerful nudges a designer can apply. In a 2011 study, the folks at User Interface Engineering (UIE) found that more than 95 percent of Microsoft Word users surveyed had not changed a single default setting in the application. Of the five percent who did, many were programmers and designers (in case you need more proof that we aren’t normal). So, unless you’re building an application just for designers and programmers, it’s critical that you get your defaults right. As Jeff Atwood puts it in his blog Coding Horror, “Defaults are arguably the most important design decisions you’ll ever make as a software developer.”

In most cases, the default becomes the permanent choice.

Choices that fall in the “good for the user and for the business” area of the choice outcome matrix are a great place to start when defining defaults.

At the time of the UIE study, autosave in Microsoft Word was defaulted to “off.” If you’ve ever lost work in Word because you forgot to save, you’d probably agree this may not have been the best design choice. Using a choice outcome matrix to explicitly map the impact of these decisions before they go live can save users a lot of frustration. Here’s what Microsoft’s map would have looked like:

If defaulting autosave to off were good for the business — maybe because of some technical impact, or because of storage space requirements — using the matrix to explicitly plot the impact would have prompted designers to mitigate these issues in advance. Maybe they would’ve communicated it more effectively to users, or would have been able to build additional features to align the user’s best interest with theirs.

Designing choices is at the core of interaction design. We must be intentional about how we present choices to users. If we can encourage them toward the best outcomes (for them and for us) we can save ourselves a lot of frustration and build trust with our users along the way.

—

“A Simple Framework for Designing Choices” was originally published in Medium on February 12, 2015.