In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman discusses the psychological phenomenon of loss aversion, which he, along with Amos Tversky, first identified back in 1979. At its core, loss aversion refers to the tendency of the human brain to react more strongly to losses than it does to gains. Or, as Wikipedia puts it, people “prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains: it is better to not lose $5 than to find $5.” This phenomenon is so ingrained in our psyche that some studies suggest that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains.

In his book, Kahneman describes a study of professional golfers. The goal of the study was to see if their concentration and focus was greater on par putts (where failure would mean losing a stroke) or on birdie putts (where success would mean gaining a stroke). In an analysis of 2.5 million putts, the study found that regardless of the putt difficulty, pro golfers were more successful on par putts, the putts that avoided a loss, than they were on birdie putts where they had a potential gain. The subconscious aversion to loss pushed them to greater focus.

If loss aversion is powerful enough to influence the outcome of a professional golfers putts, where else could it be shaping our focus and decisions?

Loss, Gain, and Iterative Product Development

Iterative product development is a process designed to help teams “ship” (get a product in front of customers) as quickly as possible by actively reducing the initial complexity of features and functionality. This is valuable because it gets the product in the hands of users sooner, allowing the team to quickly validate whether they’ve built the right thing or not. This makes it less risky to try something new. The alternative process, waterfall, asked teams to build in all the complexity upfront and then put the product in front of customers. A much riskier and potentially costlier proposition.

Iterative product development achieves its speed through a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) approach. MVP means taking the possible feature set that could be included in a product, or the possible functionality a specific feature could deliver, and cutting it down to the minimum needed to bring value to the end user. As a simplified example, imagine you are designing the first music streaming app (like Spotify). It could have lots of potential features beyond just streaming music. Things like playlists, search, recommendations, following artists, sharing, offline mode, dark mode, user profiles and so on. Building all of that would take a lot of time and effort. So an MVP streaming app might just have music streaming and search. The goal is to build something quickly that can validate if users even want to stream music in the first place before you go invest in all those other features.

Once the MVP of a product is live, a team can then quickly assess if it is successful or not, and with minimum time invested, can move rapidly to build on the initial functionality.

It is this step of the process where things can start to go sideways.

The problem starts with the concept of an MVP. We aren’t geared to think in terms of MVP. In fact, our mind takes the opposite approach. When we get excited about an idea our brain goes wild with all the possibilities (see our list of music streaming features above). We imagine all the possible value a product could deliver and then we have to lose a significant portion of that value by cutting it down to the bare minimum. It’s never easy. The unintended psychological consequence of this process is that we walk into the first version of our product with a feeling of loss. Even if our MVP is successful, that feeling sticks in our brain.

Weakness-based Product Development

The MVP process primes us to want to regain the value we believe we’ve lost. As soon as the product is live, we fall into a weakness-based, additive strategy, where we are compelled to add new functionality in order to win back our lost value (real or imagined).

This weakness-based mindset gets further reinforced when we start analyzing data and feedback. Because loss aversion causes us to focus on losses more than gains, we are more likely to gloss over positive signals and areas of strength and focus instead on the areas of the product that “aren’t working.”

Think about the amount of effort you put into understanding why something is not working versus the effort you apply to understanding why something is working. It is rare to hear someone say “how do we double down on this feature that’s working?” Instead, we strive to deliver value by fixing what we perceive to be broken or missing.

In the worst case, we even [subconciously] go looking for signals that corroborate our underlying feelings of loss.

To go back to our music streaming app, if you believed that playlist was a critical feature, but it was cut in the MVP, you are primed to put a higher weight on any feedback where a user complains about not having a playlist because it validates your own sense of lost value. Even if that feedback goes against the other signals you are receiving.

We focus on areas of weakness because they represent potentially lost value, but weakness-based product development is like swimming upstream. Areas of strength are signals from your users about where they see value in your product. By focusing instead on areas of weakness, we are effectively ignoring those signals, often working against existing behavior in an effort to “improve engagement” by forcing some new value. This is why many product updates only garner incremental improvement. Swimming upstream is hard.

Strengths-based Product Development

Strengths-based product development means leveraging the existing behavior of your users to maximize the value they get from your product. It’s about capitalizing on momentum, instead of trying to create it.

Instagram is a solid example of a strengths-based development approach. For starters, they have kept their feature set very limited for a long time. Especially early on, they did not focus on building new things but instead focused on embracing existing value. They prioritized things like new image filters and editing capabilities, faster image upload processing, and multi-photo posts. Instagram knows that the strength of its product is in sharing photos from your smartphone. They didn’t spend a ton of time enhancing comments or threads. They’ve made minimal changes to their “heart” functionality for liking posts. They never built out a meaningful web application. When they did create significant new functionality they often made it standalone, like Boomerang and Layout, as opposed to wedging it into the core experience.

Arguably the biggest change they’ve made over the years was the addition of stories. However, even that feature, while copied from Snapchat, was still an extension of their core photo sharing behavior. And, ultimately, stories increased the value of feed-based photo sharing on Instagram as well. Before stories, all your daily selfies, food shots, workout updates and so on all went into your feed. Now, much of that lower quality posting goes into stories, and feed posts are reserved for higher quality photos, creating an enhanced feed experience.

In contrast, take an example from my previous job. I was head of product for a streaming video service for almost seven years. As a subscription-based service, our bread and butter was premium video. However, many competitors in our space focused on written content, which we did not have. As an organization, we saw this weakness as a potential value loss and prioritized implementing an article strategy.

Written content did not enhance our core user behavior, but we built up justifications for the ways that it could. This is actually a key symptom of weakness-based product development. When something enhances your core strength, its value is obvious. If you find yourself needing to build a justification, it’s a sign you could be on the wrong track.

Articles never gained significant traction with our paying subscribers. They did, however, drive a high level of traffic from prospective customers via platforms like Facebook. But, the conversion rate for that traffic was extremely low. The gap between reading an article and paying a monthly subscription for premium videos was just too big of a leap. We were swimming upstream in an attempt to fill in perceived holes, but never really enhancing our core value.

On the flip side, we also developed a feature that allowed subscribers to share free views of premium videos with their friends. Capitalizing on our core strength and an existing behavior (sharing). Like articles, this drove organic traffic but also had a significantly higher conversion rate. The effect of swimming with the current.

Shifting Your Mindset

The good news is that if you find yourself in a weakness-based mindset, there are a few straight forward things you can do to break out.

- Analyze what works

When you see areas of strength don’t just give yourself a pat on the back and move on, make those areas the key focus of your next iteration. Be the one to ask, why is this working and how can we accelerate it? Stop chasing new value. You are already delivering value. Build on that.

- Move from addition to subtraction

When you look at metrics, stop looking at weak performance as something to be improved. Instead, look at it first as an opportunity to simplify. Instead of immediately asking, how can we make this better? Make the first question, is this something we should get rid of completely?

This is especially powerful in existing products. If you’ve been practicing weakness-based development you potentially have a bloated, underused feature set that’s dragging down your overall experience. What if every third or fourth development cycle you didn’t build anything new and instead focused on what you were going to get rid of? How quickly would that streamline your product and bring you back to your core strengths?

- Understand your strengths

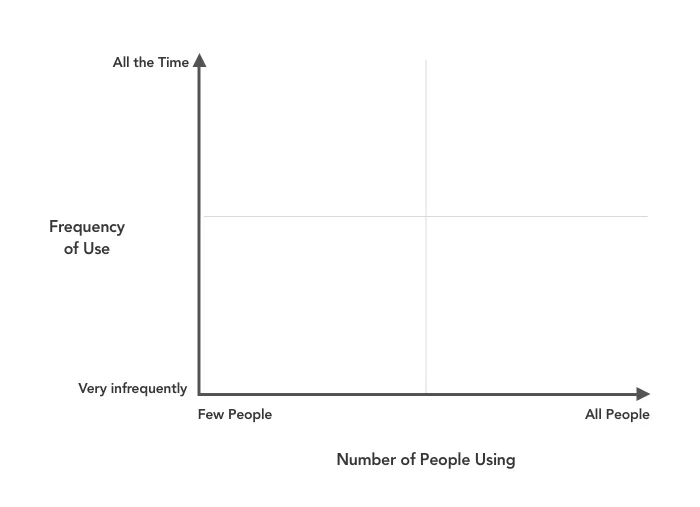

Do you know what is valuable in your product? You have to be able to answer that question if you want to step into a strengths-based mindest. If you’re not sure about the answer that’s ok, you can start with this simple matrix.

Plot your features in the matrix. Features in the upper right quadrant represent your core value. How many of your product cycles in the last three months have focused on the elements in the upper right? If the majority of your work is not happening there then there is a good chance you are practicing weakness-based product development.

If you are doing any work in the lower left quadrant you are wasting your time. Don’t waste cycles propping up weak features. Kill those features, move on and don’t fear the fallout. We get worried about upsetting users who have adopted features that aren’t actually driving our success (there’s that loss aversion again :)). It’s ok. Users will readjust, and yes, some might leave. But if you are clear on your product’s strengths and focus your efforts there, the value you gain will more than make up for anything you lose by cutting the things that are holding you back.

—

“The hidden bias in iterative product development” was originally published in Medium on June 19, 2019.